Growth in oil and gas production ends immediately in Shell’s latest pathway for staying below 1.5C, new Carbon Brief analysis reveals.

The admission that continued growth in fossil fuel output is incompatible with 1.5C is significant, because it comes from one of the world’s biggest public oil and gas companies.

Shell had previously claimed that oil and gas production could rise for another decade, even as warming was limited to 1.5C.

The dramatic shift in its new “Energy Security Scenarios” is not explicitly acknowledged, but, as Carbon Brief’s analysis shows, is hidden in plain sight.

Key to the faster fall in fossil fuel use in the new pathway is much slower growth in global energy demand, which Shell had previously insisted was all-but unchangeable.

While Shell’s new scenarios are more closely aligned with the conclusions of independent research, its 1.5C pathway still contains relatively high levels of ongoing fossil fuel use.

If the world followed Shell’s pathway, it would “overshoot” the 1.5C limit for decades, before returning below that level by using largely unproven, energy-intensive machines to suck large volumes of carbon dioxide (CO2) out of the atmosphere towards the end of the century

The fossil fuel giant stresses that its scenarios are not intended as forecasts, projections or indeed business plans. Despite being a major oil-and-gas producer, it also states that meeting global climate targets is “not within Shell’s control”.

At the same time, Shell’s new chief executive, Wael Sawan, has recently stated that “cutting oil and gas production is not healthy”. He also announced that the firm is reappraising its plans to scale back oil extraction.

New Sky

Shell recently released two new energy scenarios in response to the challenges facing the world, including the global energy crisis and rising geopolitical tensions.

The company says its “Archipelagos” and “Sky 2050” pathways ask if a world “desperate for immediate security” can also tackle climate change. Archipelagos involves global sentiment shifting “away from managing emissions towards energy security”.

Sky 2050, on the other hand, is the latest in the company’s “Sky” series that has set out pathways for cutting global emissions in line with the Paris Agreement warming target.

The first Sky scenario was launched in 2018 and only included a pathway for the less ambitious “well-below 2C” Paris limit.

The firm’s “radical” Sky scenario maintained significant fossil-fuel use even out to 2100, equivalent to a quarter of current global energy demand.

This was followed in 2021 by Sky 1.5, an “ambitious” update showing how warming in 2100 could be limited to 1.5C. It maintained exactly the same long-term fossil-fuel use and energy demand as the previous version, but with much more tree planting.

The latest Sky 2050 scenario is explained by Laszlo Varro, Shell’s vice president of global business environment and former chief economist at the International Energy Agency (IEA), in a LinkedIn post:

“In the comprehensively remodelled Sky scenario, the fossil-fuel dominated system itself is seen as a security risk and society leans forward for an accelerated transition. In Sky, clean-tech becomes like space technology during the cold war, [with] fantastic technological achievements driven not by cooperation but competition.”

Shell emphasises that it sees this new pathway as pushing the upper limits of feasibility. It describes the assumptions behind the scenario as “what we believe as technically possible as of today and not necessarily plausible”.

Shell gave very similar warnings about its less-ambitious “well-below 2C” pathway in 2018. At the time, it said this was a “radical” path that was “technologically, industrially and economically possible” – but it stopped short of saying the scenario was plausible.

In the intervening period, Shell appears to have recalibrated its assumptions.

Whereas previous Shell pathways had taken rapidly rising global energy demand as, effectively, an unstoppable force of nature, the new scenario includes much slower demand growth. This enables a much faster phasedown of fossil fuels.

At the same time, Shell’s new pathway includes more realistic – though still very challenging – assumptions around the role of afforestation and bioenergy. Instead, it includes rapid growth in direct air capture (DAC) machines to remove CO2 from the atmosphere.

Peak fossil fuels

The new Sky 2050 update involves fossil fuel production and use dropping much sooner and faster. Shell says “oil-and-gas supply peaks during the second half of the 2020s”.

In the spreadsheet published alongside its new scenarios, the company only provides data for oil-and-gas production in five-year increments.

However, Carbon Brief has extracted the data from graphics provided in its report, revealing that the peak for both oil and gas production has, in fact, already passed.

Put another way, there is an immediate end to growth in the production of oil, gas and coal – individually and collectively – in Shell’s pathway for staying below 1.5C.

In Shell’s older Sky scenarios, oil production had peaked between 2025 and 2030, as shown in the figure below (dashed line). In the new 1.5C scenario, oil production is never higher than it was in 2022 (solid line).

Output dips and flatlines until 2028 when it starts to drop rapidly – particularly for the European and North American companies operating in non-Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) nations.

Global oil production, exajoules (EJ) per year, in Shell’s new Sky 2050 scenario (solid line), compared to its previous Sky 1.5 scenario (dashed line). Shell only provides data for five-year intervals, so Carbon Brief obtained annual data for the Sky 2050 scenario from a chart provided in the company’s full report using WebPlotDigitizer. Source: Shell’s Sky 2050 scenario and Shell’s Sky 1.5 scenario. Chart by Carbon Brief using Highcharts.

In Sky 2050, OPEC oil producers use revenues from high fossil fuel prices to finance a shift away from oil-and-gas reliance.

Meanwhile, non-state backed, independent oil companies, such as Shell, take “a cautious approach” and “prefer to generate cash for their investors rather than invest in additional production capacity”. As a result, OPEC takes a larger share of production.

As for gas, Shell states: “A key characteristic of the Sky 2050 scenario is that the ‘golden age of gas’ comes to an end.” The current trend of increasing demand for liquified natural gas (LNG) is “short-lived” and global demand for gas peaks “by the middle of the 2020s”.

(In its latest World Energy Outlook, the IEA said the “golden age” of gas had come to an end, regardless of whether or not countries scaled up climate ambition to stay below 1.5C. Shell is pointing to an immediate end to global gas demand growth only within its 1.5C pathway.)

Carbon Brief’s data extraction reveals that in the new 1.5C pathway growth in gas production peaks just before the Covid-19 pandemic in 2019. This is far earlier than in the previous Sky scenario, where gas extraction continues to expand until around 2035, as shown below.

Global gas production, EJ per year, in Shell’s new Sky 2050 scenario (solid line), compared to its previous Sky 1.5 scenario (dashed line). Shell only provides data for five-year intervals, so Carbon Brief obtained annual data for the Sky 2050 scenario from a chart provided in the company’s full report using WebPlotDigitizer. Source: Shell’s Sky 2050 scenario and Shell’s Sky 1.5 scenario. Chart by Carbon Brief using Highcharts.

In the long term, the new scenario sees oil-and-gas use dropping around two-thirds lower than in the previous Sky 1.5C pathway. However, Shell still sees a significant role for both fossil fuels even in 2100.

Coal production also peaks in 2022 in the Sky 2050 pathway.

Shell’s older 1.5C pathway involved considerable coal use out to the end of the century, as shown in the figure below (dashed line). In contrast, the new 1.5C pathway sees demand for the fuel dropping fast and approaching zero by 2100 (solid line).

Global primary energy from coal, EJ per year, in Shell’s new Sky 2050 scenario, compared to its previous Sky 1.5 scenario. Shell only provides data for five-year intervals and the older Sky 2050 scenario, unlike Sky 1.5, does not include data for the years 2019-2025, which covers the drop in demand due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Source: Shell’s Sky 2050 scenario and Shell’s Sky 1.5 scenario. Chart by Carbon Brief using Highcharts.

More production?

The immediate end to fossil fuel growth in Shell’s new 1.5C scenario marks a dramatic shift from its earlier work, which had squared the circle between limiting warming to 1.5C and continuing to expand oil and gas production by invoking implausibly-large forest expansion.

On the other hand, this shift also brings Shell into agreement with the findings of multiple other 1.5C pathways.

In the influential 1.5C-compatible pathway developed by the IEA, for example, there are “no new oil and gas fields” and “no new coal mines”.

These conclusions have since been bolstered by an analysis of nearly 100 scenarios conducted by the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD). It found a “large consensus” that new oil and gas is “incompatible” with the 1.5C target.

However, Sky 2050 is still less ambitious than these other scenarios, due to its longer plateau and slower decline in fossil fuels.

It involves a drop in oil-and-gas production of just 2% and 6%, respectively, by 2030.

The consequence of slower cuts in fossil fuel use is that warming would “overshoot” the 1.5C limit for much of the second half of this century. This would raise the risk of widespread environmental and economic damage.

By contrast, the IEA 1.5C pathway and those assessed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which involve “no or low-overshoot” of the 1.5C limit, would see declines in fossil fuel use of 15-30% by 2030, according to Olivier Bois von Kursk, who led the IISD analysis.

He adds that such a slow decline means new fossil fuel production could, in fact, go ahead in Shell’s scenario:

“Meeting these production levels would imply continued development of new oil and gas fields to compensate for the natural decline rates of existing assets, a finding that would support Shell’s interests in oil and gas production.”

David Hone, Shell’s chief climate advisor, tells Carbon Brief that the company’s Sky 2050 1.5C scenario represents a balance:

“In the case of Sky 2050 and 1.5C, this represents the fastest route we could see for achieving reductions this decade and, therefore, limiting the overshoot in temperature between 2035 and 2050.”

Shell says this is an outcome that “some will consider unacceptable”, but emphasises that any more ambitious action “may not be technically feasible”.

Hone says that, in fact, a 1.5C scenario with even more fossil-fuel use would still be possible, but would result in a greater overshoot:

“Clearly, with an outcome of 1.2C in 2100 you could imagine a scenario with further fossil fuel-use than Sky 2050, then the same removals strategy, but a temperature between 1.2 and 1.5 in 2100.”

Moreover, Shell distances itself from the scenarios’ key messages and says they are “not intended to be predictions of likely future events or outcomes and investors should not rely on them when making an investment decision with regard to Shell Plc securities”.

Ultimately, it says “only governments can create the framework necessary for society to meet the Paris Agreement’s goals”.

Indeed, despite spending millions on advertising, Shell has long insisted that it has limited power to affect demand for its products.

In a 2016 interview with Carbon Brief, Shell’s then-energy scenarios lead Jeremy Bentham described the firm as “one of the bigger hairs on the tail” of the “dog” of global energy demand, saying “we can’t wag the tail or wag the dog completely at all”.

Since then, Shell has made much of becoming “a net-zero emissions energy business”, with a pledge to reduce oil production by “around 1-2% each year” following a peak in 2019. (It had no such pledge for reducing gas production.)

However, under Sawan, the company is considering weakening its climate actions. The chief executive told the Times in March:

“I am of a firm view that the world will need oil and gas for a long time to come. As such, cutting oil and gas production is not healthy.”

If Shell decides to maintain or increase production, it would join other oil majors that are rolling back climate pledges, even as they made record profits during the energy crisis. BP recently watered down its plan to cut oil-and-gas output by the end of the decade.

Low energy

In the past, Shell’s Sky scenarios have involved both fossil fuel use and global energy use at the very upper end of 1.5C pathways that other researchers have devised.

A crucial factor that enables fossil-fuel use to fall faster in the Sky 2050 scenario is its “much-reduced” energy demand. It involves global demand reaching just 641EJ in 2050, some 23% lower than the 828EJ in Sky 1.5.

In the new 1.5C scenario, the lower energy demand, shown in the chart below, is largely driven by more electrification and the assumption that buildings are made more energy efficient faster. Shell’s Varro cites “renewable-based electrification and efficiency improvements” as key priorities following the global energy crisis.

Global primary energy demand, EJ per year, in Shell’s new Sky 2050 scenario (solid line), compared to its previous Sky 1.5 scenario (dashed line). Shell only provides data for five-year intervals, and the Sky 2050 scenario, unlike Sky 1.5, does not include data for the years 2019-2025, which covers the drop in demand due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Source: Shell’s Sky 2050 scenario and Shell’s Sky 1.5 scenario. Chart by Carbon Brief using Highcharts.

Sky 2050 also involves a faster near-term acceleration of wind and solar power.

However, as the chart below shows, the shift in Shell’s pathways for these technologies is not as dramatic as for fossil fuels. (Shell’s previous 1.5C scenario already included solar power construction at the very maximum end of pathways available at the time.)

Left-hand chart shows global primary energy, EJ) per year, provided by wind (blue) and solar (red) in Shell’s new Sky 2050 scenario (solid lines), compared to its previous Sky 1.5 scenario (dashed lines). Right-hand chart shows the same but for bioenergy (blue) and nuclear power (red). Shell only provides data for five-year intervals, and the Sky 2050 scenario, unlike Sky 1.5, does not include data for the years 2019-2025, which covers the drop in demand due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Source: Shell’s Sky 2050 scenario and Shell’s Sky 1.5 scenario. Chart by Carbon Brief using Highcharts.

The new scenario also significantly scales down its assumptions for the growth of nuclear power and bioenergy, as shown in the figure below. For bioenergy, it cites “rising concerns about the availability of a large sustainable resource base”.

By 2100, Shell’s new 1.5C scenario involves just 84EJ of bioenergy and energy from waste, a reduction of 54% compared with 183EJ in its previous pathway. Similarly, nuclear in 2100 is 29% lower.

CO2 removals

These concerns over sustainability are echoed in Shell’s decision to scale back the use of tree planting and bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) in its new pathway.

Shell’s older 1.5C scenario involved “extensive scale-up of nature-based solutions”, including planting trees over an “area approaching that of Brazil”.

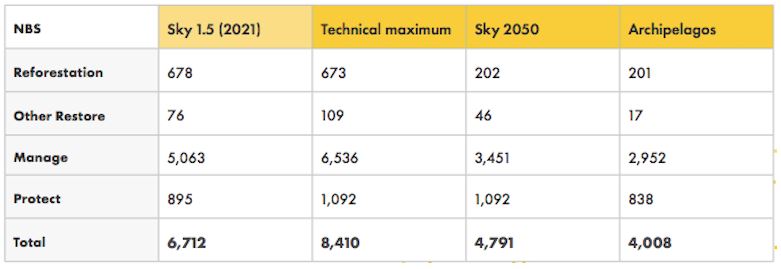

The new scenario accepts that this is an unrealistic outcome. A table from Shell’s report (below) shows that its previous Sky 1.5C reforestation target of 678m hectares exceeded the “technical maximum” global tree planting potential of 673m hectares.

Global area covered by different nature-based solutions (NBS), millions of hectares, in the three Shell scenarios, Sky 1.5, Sky 2050 and Archipelagos. “Technical maximum” refers to the global area models suggest could technically sustain such NBS. Source: Shell’s Sky 2050 scenario.

Shell takes a “cautious view” in its new scenario and undertakes “a full overhaul of the assessment of land-use change”. The “Brazil-sized” forest is replaced with a three-times smaller “Mexico-sized” forest, covering 202m hectares.

The company also emphasises the role of voluntary carbon markets in promoting nature-based solutions. It says that by 2030, an area of 20m hectares, the “size of Cambodia”, would be generating carbon credits in the Sky 2050 scenario.

Despite the lower levels of BECCS for capturing and storing CO2 from the atmosphere, CO2 removals are higher in Sky 2050 than previous versions of Sky.

This is because the new scenario relies for the first time on a substantial scale up of DAC machines for sucking carbon dioxide (CO2) out of the atmosphere. Shell says this reflects “rising hopes for engineered emissions removals” and notes:

“The CCS challenge is well suited to the exploration and production arm of the oil and gas industry, which has a unique skillset in engineering and geology.”

DAC and other technologies for removing CO2 from the atmosphere are controversial as a long-term climate solution, in part because they are popular within the fossil-fuel industry, despite remaining largely untested on a large scale.

In addition to concerns over deliverability, DAC could also have very large energy requirements. Indeed, in Sky 2050 DAC ends up consuming 13% of the world’s energy supplies in 2100.

As the chart below shows, this is more than the energy used to power every road passenger vehicle, every passenger plane or every home in the world.

Energy use by different sectors, EJ per year in 2025, 2050, 2075 and 2100 under Shell’s new Sky 2050 scenario. Source: Shell’s Sky 2050 scenario. Chart by Carbon Brief using Highcharts.

Teaser photo credit: An oil platform in Mittelplate, Wadden Sea. By Ralf Roletschek – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0 de, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=16338452